In the heart of an ancient Mayan city, archaeologists have unearthed a relic that promises to rewrite the history books. A 1,700-year-old altar, discovered in Tikal, a ruined Mayan city in modern-day Guatemala, holds clues to the complex geopolitical dynamics of the time. This ornate altar, with its bright decorations and grim contents, suggests that the Mayan city was under the influence of a powerful empire hundreds of miles away.

The Discovery

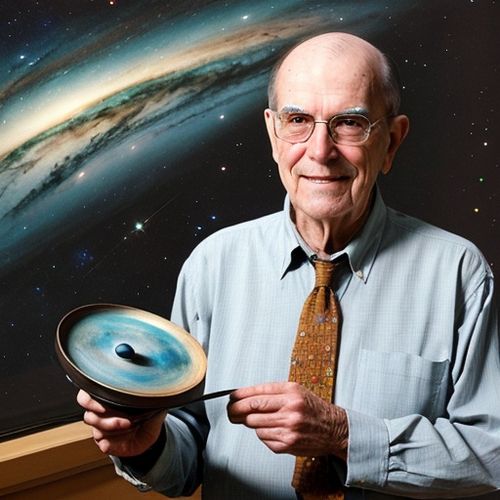

The altar, found beneath what was once thought to be a natural hill, was revealed through scans that detected hidden structures. Archaeologists, led by Stephen Houston, a professor at Brown University specializing in Mayan culture, began excavating the site in 2019. "Only a bit of this palace is visible on the surface," Houston explained. "The rest and especially the deeper layers are only accessible through tunnels excavated by archaeologists."

As they delved deeper, the team uncovered an altar adorned with faint outlines of a person wearing a feathered headdress on each panel, along with traces of bright red, black, and yellow paints. The design, which resembles representations of a deity known as the "Storm God," is more common in Teotihuacan than in Mayan art. Teotihuacan, a powerful city near modern-day Mexico City, exerted significant influence over the region.

The Altar's Origins

Despite being found in Tikal, the altar was not decorated by the Mayans. Instead, it was crafted by artists trained 630 miles away in Teotihuacan. This discovery confirms that "wealthy leaders from Teotihuacan came to Tikal and created replicas of ritual facilities that would have existed in their home city," Houston said. "This is a story of empire—how important kingdoms reached out to control others."

The altar's grim contents further support this theory. Two bodies were buried beneath it—an adult male and a small child aged between 2 and 4 years old. The child was buried in a seated position, a practice more common in Teotihuacan than in Tikal. The bodies of three other infants were found around the altar, buried in a manner typical of Teotihuacan rituals.

Cultural and Political Implications

The altar and its associated burials suggest a deep cultural and political connection between Tikal and Teotihuacan. "The sacrifices of infants fit with Mexican practices," Houston noted. "The tomb finds suggest close contact with, and perhaps an origin in, Teotihuacan."

This discovery sheds light on the complex relationship between the two cultures. Previous research had already established that the Maya and Teotihuacan interacted, though the nature of their relationship was debated. The altar confirms that Teotihuacan's influence extended far beyond its borders, with its rituals and artistic styles permeating Mayan society.

The Burial of the Altar

The fact that the altar and surrounding buildings were later buried and never built upon again is significant. "The Maya regularly buried buildings and rebuilt on top of them," said co-author Andrew Scherer, a professor of anthropology and archaeology at Brown. "But here, they buried the altar and just left it, even though this would have been prime real estate centuries later. They treated it almost like a memorial or a radioactive zone."

This treatment suggests that the Maya had complicated feelings about Teotihuacan's influence. The burial of the altar may have been an attempt to distance themselves from the foreign rituals and the power dynamics they represented.

Historical Context

The discovery of the altar adds another layer to the complex relationship between the Maya and Teotihuacan. In the 1960s, researchers found a stone inscription describing a conflict between the two cultures. Around AD 378, Teotihuacan essentially "decapitated" a Mayan kingdom, removing its king and installing a puppet ruler. This coup marked a significant turning point in Mayan history, propelling the kingdom to its most powerful point before its eventual decline around 900 AD.

The Broader Picture

The findings from this excavation reveal a tale of empires sparring and competing for cultural influence. "Everyone knows what happened to the Aztec civilization after the Spanish arrived," Houston said. "These powers of central Mexico reached into the Maya world because they saw it as a place of extraordinary wealth, of special feathers from tropical birds, jade, and chocolate. As far as Teotihuacan was concerned, it was the land of milk and honey."

The altar's discovery underscores the far-reaching impact of Teotihuacan's influence and the intricate web of power dynamics in the ancient world. It highlights the resilience and adaptability of cultures under foreign influence and the enduring legacies of empires that sought to expand their reach.

The unearthing of the 1,700-year-old altar in Tikal offers a rare glimpse into the geopolitical complexities of the ancient world. The altar's Teotihuacan origins and the rituals it represents confirm the deep influence of this powerful empire over the Mayan city. This discovery not only enriches our understanding of the past but also serves as a reminder of the enduring impact of cultural and political interactions.

As researchers continue to analyze the altar and its associated artifacts, they hope to uncover more about the lives and practices of the people who lived in this ancient city. The story of Tikal and Teotihuacan is a testament to the intricate dynamics of power, culture, and influence that have shaped human history.

By Sophia Lewis/May 6, 2025

By Olivia Reed/May 6, 2025

By William Miller/May 6, 2025

By Eric Ward/May 6, 2025

By John Smith/May 6, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/May 6, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 6, 2025

By Eric Ward/May 6, 2025

By Eric Ward/May 6, 2025

By Daniel Scott/May 6, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 6, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/May 6, 2025

By James Moore/May 6, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/May 6, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 6, 2025

By Laura Wilson/May 6, 2025

By Olivia Reed/May 6, 2025

By David Anderson/May 6, 2025

By Olivia Reed/May 6, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 6, 2025